Summary:

While the gig economy offers flexibility and the potential for higher earnings, it also harbors several significant drawbacks that might make you reconsider diving in. Here are nine concerning statistics that reveal the darker side of the gig app economy. I hope this can be a frame of reference for those who do research and those who use data-driven ways to look at gig work.

- 1. Earnings Below Minimum Wage & Personal Experience

- Progress in Minimum Wage Protections for Gig Workers

- The Data On Ongoing Challenges for Gig Workers

- 2. Lack of Benefits

- 3. Financial Stability

- 4. Underemployment

- 5. Inadequate Health Insurance

- 6. Social Isolation and Mental Health Issues

- 7. High Levels of Job Dissatisfaction

- 8. Unsafe Working Conditions

- 9. The Fight Against Hunger

- Final Thoughts

- Critical Points:

- References

1. Earnings Below Minimum Wage & Personal Experience

At one point, I was looking to make extra income and accepted an order from a popular fast-food chain. Upon arrival, I discovered the order had already been picked up. Frustrated, I forgo contacting the app company and kept working, assuming I’d still be credited for the order. To my disappointment, no credit was issued. Following that, I waited 45 minutes without receiving any new orders. Despite multi-mapping—using several gig apps to maximize earnings—the wait time was longer than usual. I realized I was working for free, earning far below minimum wage during these stretches of inactivity.

In traditional minimum-wage jobs, employees are compensated for time waiting for customers. However, many gig app drivers don’t receive pay for waiting or driving to pick up an order unless they’re actively completing a task. While some gig apps, like DoorDash’s “earn by time” option, offer compensation during active deliveries, idle periods in parking lots or between orders often go unpaid if the food is not delivered.

There was another instance when I was in a high-demand zone using the “earn by time” option, but I didn’t receive any orders. I ended up waiting for an hour without earning anything. Gig apps need to implement adjustments to ensure that workers earn at least minimum wage during these periods of inactivity, especially when using “earn by time” features.

Progress in Minimum Wage Protections for Gig Workers

As of 2024, several U.S. states and cities have implemented minimum wage laws to address the financial instability of gig work. These measures aim to provide better protections for drivers and delivery workers. Below are notable examples:

- California (Proposition 22): Passed in 2020, this law guarantees app-based drivers 120% of the local minimum wage during “engaged time” (time spent actively completing tasks) and $0.30 per mile driven. Additional benefits include healthcare subsidies and accident insurance, though drivers are excluded from employee benefits like paid sick leave and state-mandated minimum wages.1

- New York City: As of July 2023, NYC introduced a minimum wage for app-based delivery workers, starting at $18 per hour before tips, with plans to increase it to nearly $20 per hour by 2025. This provides much-needed stability for gig workers in one of the country’s most expensive cities.2

- Seattle: Gig app drivers in Seattle earn a minimum of $19.97 per hour, with some companies like DoorDash paying up to $26.40 per hour to comply with local laws. Seattle also mandates paid sick leave for app-based workers, ensuring additional protections.3

- Minnesota: In 2023, Minnesota passed a law requiring Uber and Lyft to pay drivers at least $1.45 per mile in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area and $0.34 per minute of active driving. This legislation is designed to help gig workers achieve greater financial security.4

The Data On Ongoing Challenges for Gig Workers

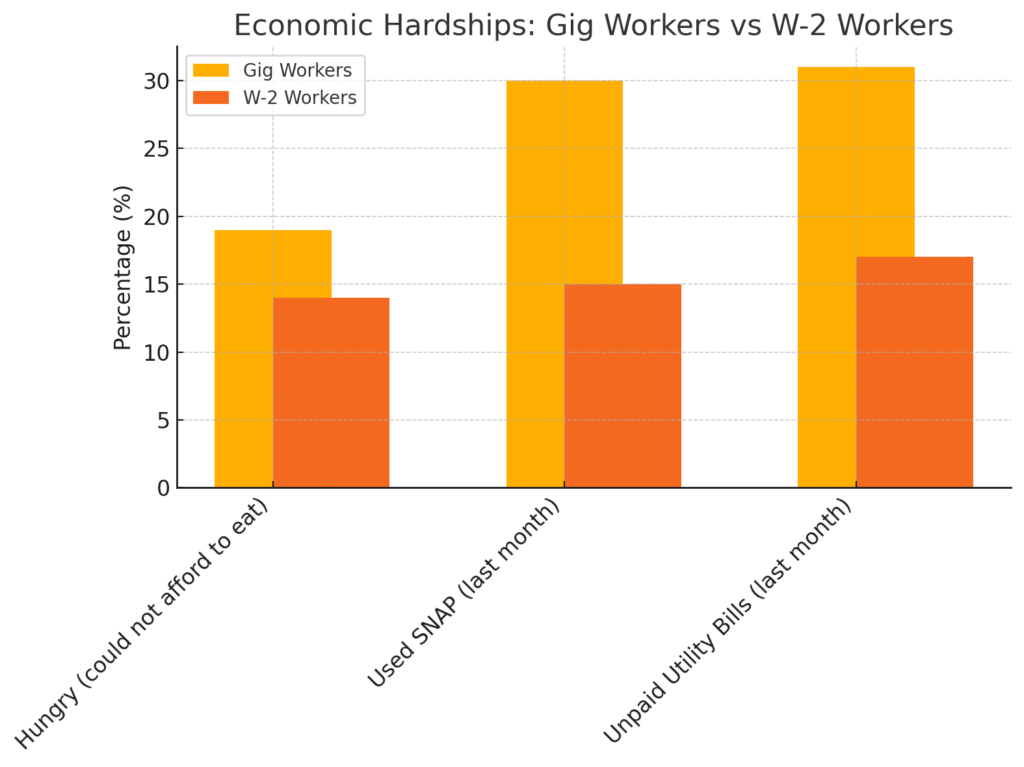

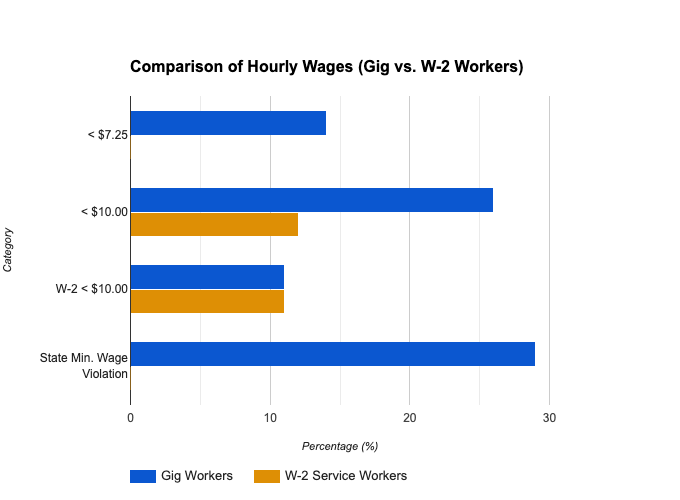

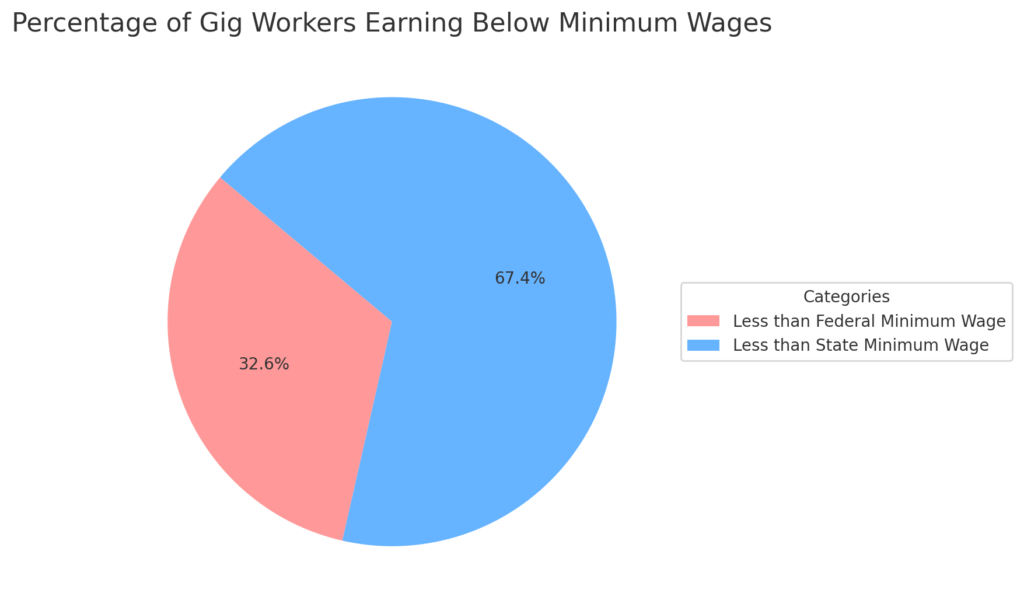

Despite these advancements, many gig workers across the U.S. face financial difficulties. In 2022, 1 in 7 gig workers earned less than the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour, and nearly 30% earned less than their state’s minimum wage. These statistics underscore the ongoing struggle for fair pay in the gig economy.5

The comparison of hourly wages to gig workers reveals disparities:

While new laws in select regions are promising, they highlight a broader need for nationwide standards to ensure financial stability and fairness for all gig workers. This remains a critical area in the evolving work landscape for researchers, policymakers, and gig workers.

2. Lack of Benefits

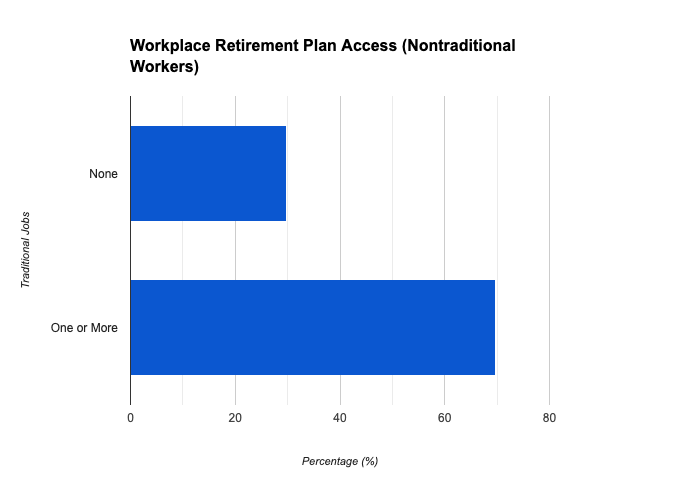

“Only 29.8% of nontraditional workers with no traditional job had access to a workplace retirement plan. By comparison, 69.7% of nontraditional workers with one or more traditional jobs had a workplace plan such as a DB, DC, or another plan“(Pew Trusts, 2021).6

This gap underscores the lack of financial safety nets for independent contractors, freelancers, and gig workers, who often rely on inconsistent income streams and face incredible difficulty saving for retirement. In the real world, this disparity translates to increased financial insecurity for nontraditional workers, particularly as they age and can no longer work.

The lack of access to employer-sponsored retirement plans places a heavier burden on these individuals to independently save for the future, often without the same tax advantages or matching contributions offered in traditional employment settings. Addressing this gap is critical to ensuring long-term economic stability for the growing number of people engaged in nontraditional work.

3. Financial Stability

A key statistic in a study by Dmitri K. Koustas is that households’ net balances (total liquid assets in bank accounts and checking accounts, net of credit card debt) decline by over $400 in the period before starting a gig job, stabilize when starting a gig economy job, and recover slightly over the past period. This statistic highlights households’ financial distress before entering the gig economy, indicating that many individuals turn to gig work as a response to economic hardship (Koustas, 2019).7

Pre-gig work conditions are essential for the context of why people enter into this line of work. Without adequate help over just four months, there can be struggles. An additional study highlights significant financial challenges faced by gig workers.

A study by the Commonwealth revealed that 16% of Americans have earned money through gig platforms, with this figure rising to 25% among those with low incomes. Additionally, gig workers are more likely to experience financial instability, with 80% of Cohort 2 experiencing financial hardships of over $1,000 before joining the pilot program (stipend during the study).

Furthermore, the study shows that gig workers often need more savings, with 41% of Cohort 1 and 44% of Cohort 2 having no savings when they joined the program (Commonwealth, 2022).8

“As a gig worker, I counted at least five times I faced a significant setback working in the gig economy. “- KemeticMind

I propose a stipend for all gig app drivers to help them every three months, divided by the end of each quarter to ensure they can sustain themselves and their finances.

4. Underemployment

Despite the promise of flexibility, many gig workers still need to be employed. Nearly half (49%) of gig workers earn less than $50,000 annually, and many work fewer hours than they would prefer (Daugherty, 2024).9

- For example, 41% of gig workers spend less than 10 hours weekly on their gigs (Daugherty, 2024)

Three critical statistics in a study by BMC Psychology highlighted the following:

- Income Trends: “The relationship between W-2 and 1099 income is reliably inverse—when participants lose income from their W-2 jobs, they need to pick up 1099 work to supplement”.

- Financial Hardships: “At the program’s close, most participants experienced financial hardship. Typically, these hardships were expected; participants needed support to pay rent, utilities expenses, and unpaid bills. For many, it was standard to experience multiple hardships over the four months”.

- Income Health: “Direct cash interventions can immediately decrease the need to use predatory products, such as payday loans or cash advances. However, overall usage of these products is higher for those who earn more income (i.e., those with more income that they need to access ahead of payday). This demonstrates the general inadequacy of wages for workers living on low incomes”.10

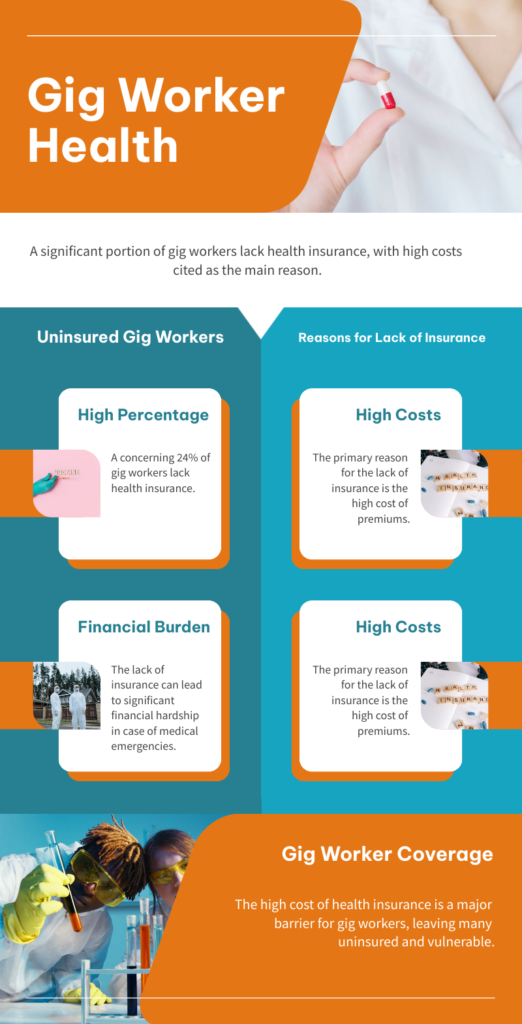

5. Inadequate Health Insurance

Access to affordable health insurance is a significant barrier for gig workers. A survey of over 4,000 gig workers found that 24% lacked health insurance, with 58% citing prohibitive costs as the primary obstacle. This lack of coverage leaves many gig workers vulnerable to high medical expenses and financial crises.11

6. Social Isolation and Mental Health Issues

It is odd to go into a restaurant and see everyone else having a good time. It can be isolating and make you think about your friends and family when you’re at work. I’m sure some employees feel the same thing.

According to a study by Li & Wang (2022), using data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS), quote:

“Although gig workers obtained the manifest and financial

benefits of employment on mental health and life satisfac-

tion compared with the unemployed, they did not obtain

similar financial and social connection benefits compared

with traditional workers”(p. 7).12

- How can this have an impact in the long term?

7. High Levels of Job Dissatisfaction

For me, the dissatisfaction stemmed from needing more income stability. The pay can go up and down, which doesn’t support the thought of being at ease on the road. Here is another experience from a YouTube channel, Jamie Linear:

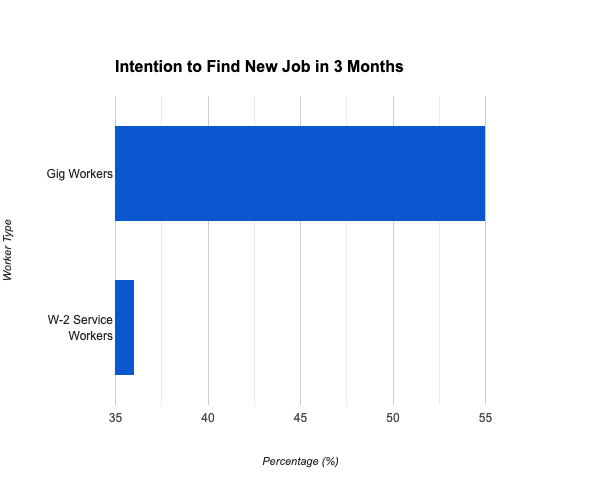

Edison Research mentioned the following:

“Our research shows that there are two gig economies: one where gig jobs serve as the primary livelihood for employees, and one where they provide supplemental income. The 44% of Americans working in the gig economy who depend on gig work as their primary source of income show deep economic anxiety, which merits further study,” said Edison Research President Larry Rosin.”13

I could echo that sentiment when the gig economy was my primary income. “What If” was always in my mind, just attempting to be independent and not needing financial help.

A few key statistics from this study include:

Key statistics from a survey mentioned that 80% of respondents said they couldn’t handle a $1,000 unexpected expense.

Many gig workers experience low job satisfaction due to the instability and lack of security associated with gig work. Only 44% of gig workers consider their gig work their primary source of income, indicating that many rely on it as a supplementary source rather than a stable livelihood (Edison Research, 2023).

Leave a Reply